Rhabdomyolysis - From the London Blitz to Statins

In 2001, cerivastatin, with the main brand name of Baycol, was taken off the market. The voluntary withdrawal from sale of this statin, by the pharmaceutical company Bayer A.G., was due to 52 deaths from drug-related rhabdomyolysis (pronounced rab-doe-my-o-lie-sis) that resulted in renal (kidney) failure.1

In 2001, cerivastatin, with the main brand name of Baycol, was taken off the market. The voluntary withdrawal from sale of this statin, by the pharmaceutical company Bayer A.G., was due to 52 deaths from drug-related rhabdomyolysis (pronounced rab-doe-my-o-lie-sis) that resulted in renal (kidney) failure.1

Rhabdomyolysis occurs when muscle — mostly skeletal muscle — rapidly breaks down and enters the bloodstream. Some of these broken-down muscle products, including the protein myoglobin, block the kidney tubules. In extreme cases of rhabdomyolysis, the kidneys can fail completely. Untreated, this renal failure usually leads to death.

Rhabdomyolysis has occurred throughout human history and is also known by the name ‘crush syndrome.’ Crush syndrome was first reported on by a Japanese physician named Seigo Minami who looked at the records of three soldiers who had died during World War I of renal failure.2

Renal failure came as a direct result of muscle destruction with muscle debris ending up in the kidneys causing them to stop functioning. The injuries had come from the blast trauma of exploding munitions.

Crush syndrome — death from renal failure — had also been seen in people who had suffered severe injuries after natural disasters, particularly earthquakes.

Rhabdomyolysis was first formally identified and described in the British Medical Journal of March 22nd 1941. E.G.L. Bywaters and D. Beall published their observations of four victims with severe crush injuries following air raids on London during World War II. As a result of publication of these findings, crush syndrome is also known as Bywaters’ syndrome.3

The German air raids on the United Kingdom during World War II, known as the Blitz, targeted cities, with residential areas being particularly hard hit. 40,000 civilians were killed during this air offensive, half of them in London, with a million homes destroyed or damaged.

Crush injuries from falling masonry were common. It was not unusual for people to be trapped in a collapsed house or other building for many hours or even days before being rescued.

Of those that survived a building collapse from a bomb, but had been trapped under a mass of bricks and rubble for hours, many developed severe complications a day or two after being admitted to a hospital.

These complications would manifest as shock — due to fluid loss where the crush injury had occurred — followed by a spike in blood levels of potassium and urea.

These patients were only able to pass a small amount of urine which was dark brown in color. Dialysis — the process of filtering waste and excess water from blood — was not yet available, so many of these patients died.

Rhabdomyolysis — caused by crush injuries suffered during explosions and earthquakes — remains a leading cause of death among survivors today, particularly in areas with limited availability of medical care, equipment and facilities.

Many different causes of rhabdomyolysis other than crush injuries have been identified including electrical shock, thermal imbalance, cocaine use, certain toxins, electrolyte and endocrine disorders and more recently, statin drug use.

So what is the connection between rhabdomyolysis as a result of crush injuries and rhabdomyolysis from statins? How do statins cause rhabdomyolysis in some people?

Just as with crush injuries and the other causes of rhabdomyolysis, statins can cause skeletal muscle (the muscles that control movement) to break down.

The symptoms of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis are severe muscle pain and aches over the whole body along with muscle weakness and dark colored urine. Anyone experiencing these symptoms should seek immediate medical attention.

The only countries that currently allow pharmaceutical products to be advertised directly to the consumer are the United States, New Zealand and Brazil.

People in those countries will be familiar with the typical warning at the end of statin commercials along the lines of ...tell your doctor if you feel any new muscle pain or weakness. This could be a sign of rare but serious muscle side effects. These ‘rare but serious muscle side effects’ can (and sometimes do) lead to rhabdomyolysis.

Rhabdomyolysis was ten times as likely to occur with cerivastatin (Baycol) than the other five approved statins at the time.4 But this didn’t mean that the removal of cerivastatin from the marketplace eliminated the risk of rhabdomyolysis from taking statins.

Just because other statins had only a tenth of the likelihood to induce rhabdomyolysis did not mean the threat had gone. With many more patients taking statins compared to the Baycol era, overall cases of statin induced rhabdomyolysis have risen.

In 2006 I obtained all the atorvastatin associated MedWatch Adverse Drug Reports for the period 1997 to 2006. From this resource I counted 2,731 cases of rhabdomyolysis hospitalizations for the period 1997 to 2006 from atorvastatin alone.

Amer Ardati et al5 previously had estimated the death rate from all statin associated rhabdomyolysis at 12 percent suggesting an estimated 307 deaths during this time period.

From the 1st. July 2005 to 31st March 2011, FDA MedWatch records were reviewed by Hoffman et al6 finding 8,111 reports of all statin associated rhabdomyolysis hospitalizations during this study period.

Groups at higher risk of rhabdomyolysis when taking statins are the elderly, those with hypothyroidism and those that are also taking fibrates.

The risk of rhabdomyolysis from taking statins remains very low as a percentage of those taking a statin, but still very real. The stronger the statin and the higher the dose, the greater the risk.

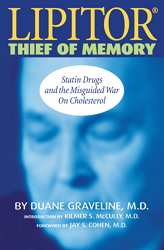

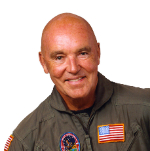

Duane Graveline MD MPH

Former USAF Flight Surgeon

Former NASA Astronaut

Retired Family Doctor

References:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11806796?dopt=Abstract

- http://www.medscape.com/medline/abstract/16491906

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2161734/

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC59524/

- Ardati A, Stolley P, Knapp DE, Wolfe SM, Lurie P. Statin-associated rhabdomyolysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:287. doi:10.10021pds.10530.

- Hoffman KB, Kraus C, Dimbil M, Golomb BA. A survey of the FDA's AERS database regarding muscle and tendon adverse events linked to the statin drug class. PLoS One 2012;7(8):e42866. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042866.

January 2016